|

||||||||||

1944 | January 1945 | February 1945 | May 1945 | 1955 |

||||||||||

| 1944 Dad was stationed, in November 1944, at Molsworth, England. He navigated B-17 bomber missions over Germany. It took guts to navigate a plane filled with gasoline and packed with bombs into an intersecting star pattern with eighteen-year-old pilots criss-crossing on take-off. The crews sang “Off we go into the wild blue yonder, flying high, into the sky…” at full force as they taxied to the runway. And it took guts to fly in formation on mission after mission into the wartime hazards of the sky, dropping bombs on strategic German infrastructure while dodging enemy fighter planes and exploding flak. On both sides of the line, young men were risking their lives for what they had been told was their duty to their country. This selfless abandon was driven by what? by drill? by community? by patriotism? over and over again. Maybe it was by the mere fact that it was what everyone else was doing? There was nothing funny about it, but humor rippled through every conversation about this merry little war. Their “catch 22” was that while they were being shot at on each mission, they had to complete a set number of missions to get sent home. Dad navigated through screeching and whistling shells exploding all around him in the clear nose of a B-17. When did his youth end? Was it his first apocalyptic mission? Was it one moment or a long series of experiencing, or making, the depths of hell? Every five missions they’d get a three-day pass. Dad went to the theatre in London or for a rollicking weekend to forget the flying circus. Dad’s friend Curly, a young British kid, invited Dad to stay at his family’s house in London. Then, he went back to his 13th, 14th then 15th missions. It was hard to guess when the vertigo set in. Was it from the constant migration across the eastern U.S. with changing labels: Navy officer; Army corpsman; 2nd Lieutenant (dog tags: 0 2065589); pilot; navigator, 303 Bomber Squad; POW (number: 9324)? Or from flying five miles above the ground in unpressurized planes? “I’m never going to get into one of those,” Dad stated firmly while gesturing towards one of the first helicopters. There were guys who had finished 50 missions and thought they’d be going home. Instead, the target was moved to 60. |

|

|||||||||

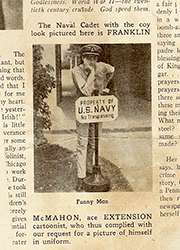

Navy sign published in Extensions magazine. c.1944. |

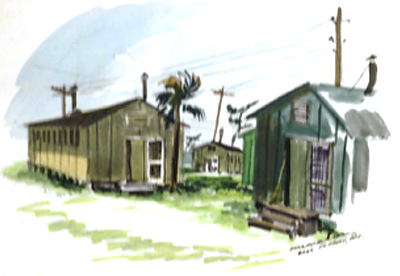

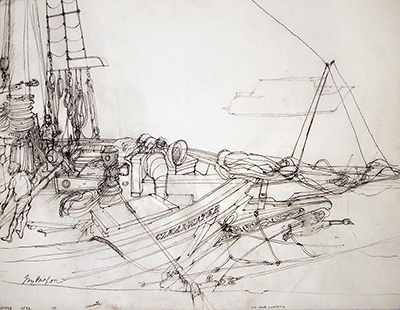

While stationed in Molsworth, England, Dad drew cartoons and mailed them to Extensions magazine in Chicago. c. 1944. |

|||||||||

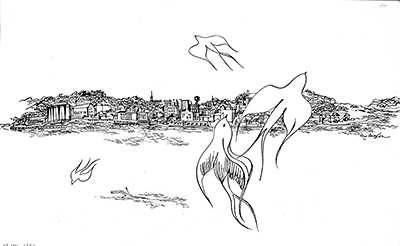

London Bridge, created in United Kingdom More caption to come |

||||||||||

January 13, 1945 By proper procedure, Dad was to be the first one out of the plane. He looked hard at the .45 pistol and realized he wasn’t going to shoot his way out of Germany. Instead he pocketed his silk map of the German landscape. The bell rang and he kicked out the escape hatch. He looked through the clouds to the forest from four miles up, thought about the fire in the wing, the plane exploding, his lack of oxygen, the nine guys behind him and… jumped. “Jesus, Mary and Joseph, spare me.” Dad gasped a thin breath of a freezing blast of air at 200 mph. That kept him from passing out. The free fall stripped off a boot. Shrapnel sliced at his coat and face. Blood froze, as did tears. He’d been up here before, but not in this flak-filled arena. Dad focused on the pull chord of his parachute. He knew the guys at Fort Meyers that packed the parachutes; he hoped they’d packed this one right. A lot of the guys free fell over 10,000 feet to get to oxygen before pulling their cord. Dad didn't remember waiting, but may have counted to ten—one one-thousand, two one-thousand, three one-thousand—to clear the plane before he pulled the ripcord. The parachute opened; silk straps flapped in his face. Then there was a tremendous jolt. Some time had passed, and the plane had dropped a distance. He could now breathe. He had time to get his wits together. He pulled the shroud lines on the sides of the chute to aim a landing. He dropped through the icy smoke, past the smell of burnt metal as the humidity rose. Then he smelled hay and manure, and whiffs of evergreens and wet, mossy stones. The smell of hearth fires triggered vague memories churning of jealousy, anger, desire, home. Dad landed silently in broad daylight, smack dab in the middle of a soccer field in Pirmasens, Germany. Civilians, police, soldiers, kids and stray dogs saw him, and he saw them. They were running down the street towards him as he landed. He was scared. He struggled to get the parachute harness off, then sprinted with only one boot. Lopsidedly, and feeling he hadn't had enough oxygen, he ran through the snow into a cave near the soccer field. In the cave, he ripped the inside of his jacket sleeve and stuffed the silk map down to his elbow. The Gestapo was a concern, but more immediately he knew the German citizens thought of him as a terror flugzeuge. His primary concern was about the civilians who might pull him apart, limb from limb. Frayed nerves stood on-end, seemingly outside his skin. Fear smelled like metal, permeated his damp, musty stone shelter. He surrendered to German soldiers with relief. This parachuting artist landed in the middle of the living hell of Germany with only one boot and the Geneva Convention to protect him. |

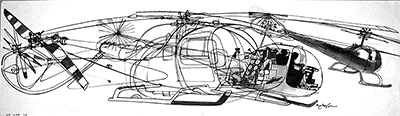

Helicopter Encaustic on Masonite c. 1957. 9” x 22”  Helicopter 3 c. 1957  German Landscape Watercolor on paper. c. 1945.

|

|||||||||

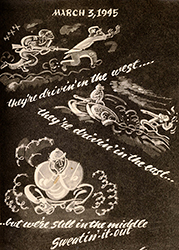

Still in the Middle Cartoon. 1945. |

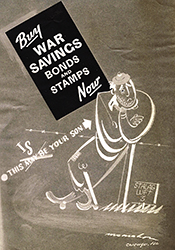

Savings Bonds 1945. |

|||||||||

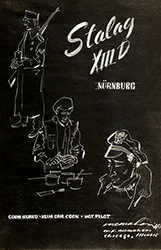

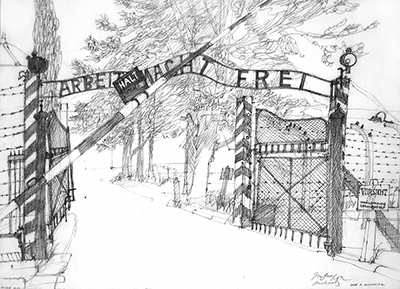

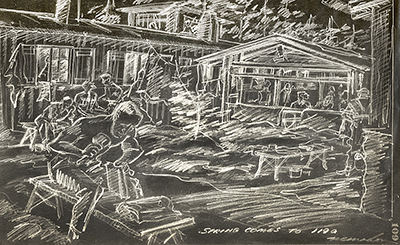

| February 1945 Dad was force-marched out of the gray of the camp into a foot of wet spring snow. “Be careful what you wish for, it could get worse,“ he’d said. The hundred -mile march from Stalag XIII D near Nuremberg to Stalag VII A at Moosburg landed him close to both the not-yet-known-about gas chambers at Dachau and the always prominent lure of a possible escape to Switzerland. He was marched from Nuremberg to be moved away from the liberating Allied Third Army. Dad’s replacement boot didn’t fit well. The eyelets were kept together with a length of wire. The 15 miles of daily trudging pinched his toes and chafed at his insole, heel and the ball of his foot. Painful sores blistered and could become fatally infected. The boot opened the blistering wounds every morning; they bled all day. There was occasionally a soapy cleanse. Dad had packed Red Cross jelly, cigarettes and scraps of soap for the forced march. He traded these with the ‘volks’ along the way for eggs, vegetables and bread. Don’t confuse the ‘volks,’ ordinary folks, with the ‘volkisch,’ or racial-nationalists. The 12-hours-a-day march, while it was long—over a week, featured about the best provisions he’d eaten while being a prisoner. The villagers were eager to trade with him. They were beyond hunger too. Dad saw the want and sorrow that had rushed over the outside world like a deluge. It would take time to recede. His exchange of cigarettes for eggs with the villagers offered something fresh to eat, but also someone other than prisoners to connect with. Was it a connection to life? or at any rate, hope? He liked the villagers. His woolen sock was his ongoing concern. It kept embedding in the numb sore at the back of his heel and would rip open scabs each night. Maybe tomorrow he’d try a piece of cotton undershirt between the sock and the foot? Through the fuzzy, blinding, disjointed whiteness, Dad saw a Todt worker—a conscripted laborer— just a boy in ragged clothes, crawl into a garden for a left-over potato or spring garlic. Just under the fence, the boy collapsed and lay there, thin, wasted and covered in vermin. That poor boy couldn’t feel the lice and maggots crawling from his hair, over his eyelids, and down his face. To do this to mere boys! Maybe this was when Dad became the least judgmental person on earth. He saw that eachperson was just striving to survive—Volks, Todts, Air Force and Goons. |

|

|||||||||

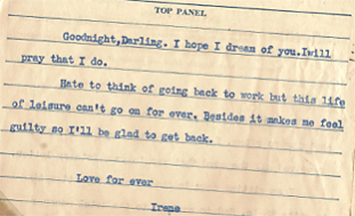

May 1945 They dined, actualizing the life they had imagined when apart, at Chez Paree and Chez Paul, Armandos, the Erie Cafe, Riccardo’s and Mona Lisa’s. They gleefully and somewhat guiltily courted. Dad had no injuries; Mom had savings. While planning their wedding in Rush Street restaurants, they embraced their freshly found love. They laughed at their starting anew and the mistakes made during their growth to become one. Free at last to be together, they reminisced about high school, tracked who was returning, who was still in Japan. Just as Mom was telling Dad that her American Airlines job would no longer be available after their wedding day, the organ grinder’s squirrel monkey leapt onto her shoulder and tried to pinch her hat pin. Little toes gripped her shoulder, tiny fingers caught in her hair, the “che-che-che” horrified her. Dad lifted the leashed monkey and handed it back to its grinder at arm’s length. They danced on and on, to their July 27th wedding day at Our Lady of Sorrows Basilica on Jackson Blvd. As Dad dressed in his lieutenant’s uniform that morning, he decided that none of the invited guests could possibly know the satisfaction that was his. He was alive and he was marrying Irene. Irene had sent Rita and Charlotte to find her a new stocking when the catch on the garter had caused a run. She’d barely had time from her last flight to pack for the honeymoon. Rita and she gathered some of their best cleaned sweaters, blouses and skirts. The sisters still exchanged clothing. The Catholic church sent them scapulas with advice to pray to Blessed Mary, “My Mother, my confidence.” His hung beneath his uniform, hers beneath her wedding gown. In a hanging bag was her post-wedding dress for the Knickerbocker Hotel reception. In another bag was the borrowed long wedding dress train Rita and Charlotte would attach at the Basilica. Irene had purchased the simplest ivory dress she could find.

Dad continued to cartoon at Extension magazine during the day and to take night courses at the Institute of Design in the old Historical Society building on Ontario. Lazlo Maholy-Nagy said art was about tools and perception. The artist was a witness, and his media could be print reproduction and film. The New Bauhaus recreated Chicago as the city grew exponentially with the solidity of molten steel and an ambiguity of corruption. Dad learned methods to create and replicate his works of art and incorporate them into society. Reproduction was identified as an opportunity. Ideas floating in the air were to be snatched and utilized to effect societal change. The artistic individual could connect to, interpret and bond with his or her community. At its essence, Art (with a capital A) was the act of making art and the serious play of experimentation. Dad learned that art, by its nature, is political. Making art acts as a corrective to greed and power. By uniting art and everyday life, the artist can change the world, can make it better. Vision was the 5% inspiration. After Dad unfolded and set his 8” x 10” wire and canvas camp stool on the sidewalk, he sharpened his pencils with a straight edged razor and sat down to draw. Now came the 95% perspiration when the pencil hit the paper. He had to let go and allow his will to take over for his art to make his vision; “Put your pencil on the paper and make your line with authority.” He drew elegant, but emphatic, lines connecting time and place to capture history. His impeccable humor and cartoon enhancement rippled through in his Artist Reporter style. He submitted to the process of art that allowed his eye, consciousness and hand to make an image. He became his own tool. He became one with the pencil and paper, and his flow of energy prevailed. Dad got lost in the 22” x 33” arches paper. He could dive into the image and be surrounded by it when the edges curled up. Back in the studio, he painted in watercolors, weaving these ideas into art while listening to Paul Rhymer’s radio show, “Vic and Sade,” whose quirky sense of humor was unmistakably Midwest. |

|

|||||||||

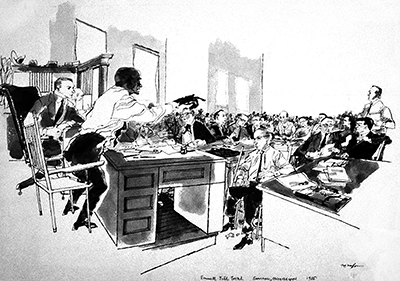

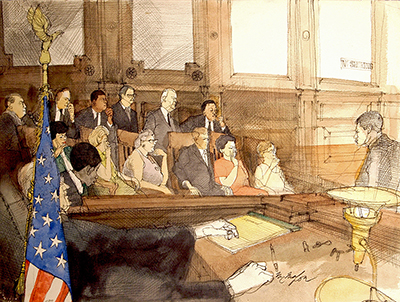

1955 When his oldest son was eight, our dad landed in Sumner, Mississippi, to cover, with drawings, the Emmett Till trial for Life magazine. “Historically, artists had been in the courtrooms before the invention of the camera, so there was no precedent for a photographer,” Dad explained. “The judge would make the decision, and generally speaking photography wasn’t allowed.” He shaved cleanly in the morning, tightened a tie and slipped into a suit coat to fade into the press section. Southern whites were still peeved about the recent Brown vs. the Board of Education federal decision ensuring African Americans an equal education. Amidst Northern court reporters, Dad hoped the trial onlookers would think he was just another reporter doodling or taking notes. The story unfolded about Emmett Till, a black 14-year-old from Chicago who had been taught to whistle to calm his stuttering. After struggling through b-b-b-b- to ask Mrs. Bryant for bubble gum, he let out a bit of a whistle to calm himself. Dad had relaxed his judgment to allow his compassion to guide him. He grasped for a vision that would tell the story of the trial. He captured a coifed and elegantly dressed Mrs. Bryant in his hand sized spiral notebook. He set the tone of non-sympathetic white male jurors in a wash of ink. Accused of flirting with a young white grocer, Emmett was abducted from his uncle’s home that night. He was found, beaten, shot and mutilated, in the Tallahatchie River. Then the dramatic moment happened! Dad captured with pencil on paper Mose Wright, Emmett Till’s uncle, rising up and pointing to identify the two white men on trial. “When he pointed like that, Mose Wright had the guts to shuck 300 years of history,” Dad explained. They were the men who had abducted and lynched Wright’s visiting nephew. Dad’s cartoon background informed him to make something of the shaky, outstretched and elongated arm, the force of gesture in the stance, the suspenders on the pants. When he and a reporter walked across the street for a cup of coffee, they were surrounded by a few white male citizens and roughly asked, “Why don’t you go back up North and leave us Sumner folks alone.” In his hotel room, Dad redrew the sketches on a larger sheet of paper. In that moment, his heart and mind guided his hand to tell through publishing what he witnessed of this southern atrocity. Dad mailed the drawings in a flat brown package from the hotel desk to Life. “I wasn’t thinking ‘history’ when I did the Till trial; I did it as a job,” he explained. He had to rush to get the artwork finished by Life’s Saturday night deadline. In April 1957, lucky number seven, newborn Margot Ann McMahon was brought home from the hospital to an Edward Hemrich designed home. Through my blurred vision, as my eyes came into focus, I observed the visceral connection of the interior with the surrounding woods through a thin veil of glass, framed in cedar. Dad’s studio was just a short walk through the woods. Six sets of blue-eyed brothers and sisters peered over my crib rail while Mom was in a hubbub. All summer she was packing for our upcoming year in Spain. Before I was six months old, we nine were on a ship, headed to a Spanish farm in Torremolinos. Mom, who had long ago traversed the country by air, felt like she’d never see Europe with seven children underfoot. Dad was reacting to McCarthyism and eagerly arranged to take the whole family to see post-war Europe. He wanted time to continue his encaustic series. We nine boarded a boat and settled in Torremolinos, Spain, where bull fights, home-farmed turkeys, and picnics in Portugal became our life. I was called “Bonita Chickadina” by my brown-eyed Spanish-speaking nanny, while my parents toured Europe in an “If its Tuesday, this must be Belgium” mode. Dad layered wax and oil paint on masonite panels, then heated the mixture, melting it into translucent symbolic encaustic images of helicopters, farm equipment and shoppers on escalators, while I learned to crawl and walk. |

|

|||||||||

| —page top— | ||||||||||

The Eternal Optimist | Parachuting Artist | Cut the Flak | Blog | Home |

||||||||||

For further information or to purchase art please contact: Margot@FranklinMcMahon.net MargotMcMahon.com

|

||||||||||